Apples growing in the Frank L. Harrington Sr. Orchard

By Robert Burgess

BOYLSTON, Mass. — The next chapter in the story of a very special preservation apple collection begins soon. Our Frank L. Harrington Sr. Orchard, which displays the Davenport Collection of pre-20th century heirloom varieties, has reached the end of its intended lifespan and requires restoration. With the help of some longtime friends and leading apple experts that effort begins this fall.

(Read more about New England Botanic Garden at Tower Hill’s orchard in the New York Times.)

The importance of this orchard has always resided in not the physical trees themselves, but the antique varieties that were developed by farmers, cider brewers, chefs, and orchardists generations ago. The 119 varieties at New England Botanic Garden at Tower Hill include such gems as the Calville Blanc (named in 1598), Sops of Wine (circa 1600), Rhode Island Greening (c. 1650), and Esopus Spitzenburg (c. 1790). Those varieties have been preserved by dedicated orchardists in the decades since. Without those people, these living history treasures might have been lost forever.

The importance of this orchard has always resided in not the physical trees themselves, but the antique varieties that were developed by farmers, cider brewers, chefs, and orchardists generations ago. The 119 varieties at New England Botanic Garden at Tower Hill include such gems as the Calville Blanc (named in 1598), Sops of Wine (circa 1600), Rhode Island Greening (c. 1650), and Esopus Spitzenburg (c. 1790). Those varieties have been preserved by dedicated orchardists in the decades since. Without those people, these living history treasures might have been lost forever.

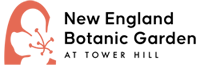

It’s unlikely you’ve ever eaten an apple from a tree grown from seed, unless you were foraging in the woods. Each named apple has a backstory. Once upon a time someone bit into that apple and decided they wanted to replicate that taste. However, the seeds in that apple received pollen from different varieties brought to the apple blossom in the spring by busy bees and if planted would grow up with the parental attributes of those different trees. The secret to reproducing the exact flavor, color, size, and texture of the apple you just bit into? Grafting.

Grafting is the process of joining two plants together to grow as one. The upper portion of the plant is the scion and it determines the qualities of the fruit. The lower portion is the rootstock, which determines the vigor, height, disease resistance, and lifespan of a tree. With apple trees, newly sprouted branches are pruned from a desirable variety and are carefully grafted to the preferred rootstock of another tree. Experts use knives to cut notches where the plants of the same species can join, the roots providing water to the new branch, the leaves of the new branch sending nourishment down to the roots. In fact, some people enjoy grafting multiple varieties of apples to the trunk of one tree; it works as long as we’re talking apples to apples, and not combining different genuses, say an apple scion to a cherry tree trunk.

thisnzlife.co.nz image

That Red Delicious apple at the grocery store? It’s derived from the same tree selected years ago and all the trees of that variety have come from scionwood bought, sold, and traded throughout the decades. Not seeds. Johnny Appleseed, born nearby in Leominster and famous for spreading apples across the United States during the 19th century, was ultimately promoting cider. Personally against grafting, his trees produced apples that were only suitable for fermenting. And in those days, when the procurement of clean drinking water was a difficult task, cider was especially important.

Speaking of seeds, you may have heard of seed banks. There’s a famous one in Norway, commonly known as the Doomsday Vault, ready to be tapped into if some calamity wipes a species out. Closer to home, the Native Plant Trust, headquartered at Garden in the Woods in Framingham has a Seed Ark that protects seeds of rare, native New England plants, a back up plan to preserve biodiversity. Seed banks are particularly important for field crops. Those seeds have been protected from the mixing of pollen from passing bees, so that the wheat, pepper, squash or other commodity will grow true to the desirable variety of produce. There is no seed vault for apples and other fruit trees. Instead, they are preserved in living orchards, like the one at New England Botanic Garden at Tower Hill. But how did all those old-fashioned varieties end up here?

Where did New England Botanic Garden at Tower Hill’s apple trees come from?

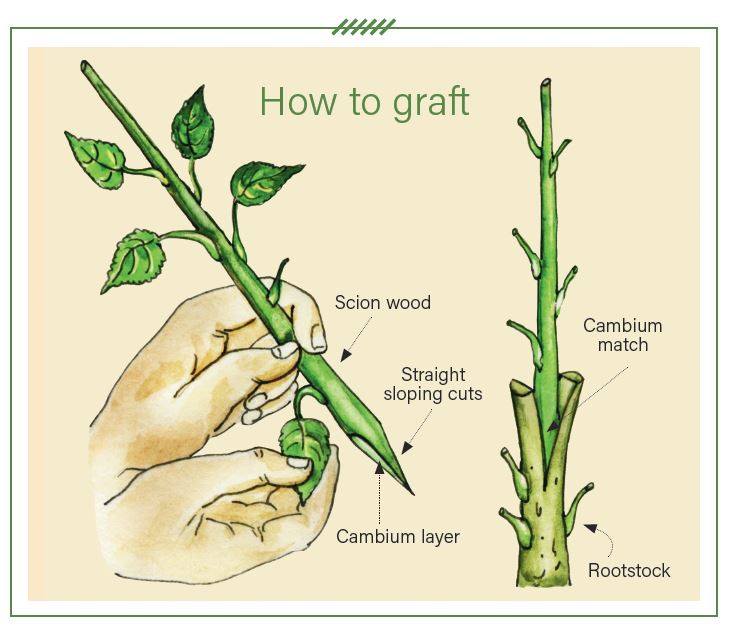

Portrait of Stearns Lothrop Davenport.

During the Great Depression, Stearns Lothrop Davenport (1885–1973), working for the Massachusetts Department of Food and Agriculture, directed a Work Progress Administration (WPA) project charged with felling abandoned apple trees that were harboring insects and diseases and negatively affecting commercial orchards. Davenport began to worry he might be turning the last varieties of some apple trees into firewood, losing their unique qualities, unusual histories, and genetic material forever. He began grafting scionwood from the rare varieties he encountered to trees in his own orchard at Creeper Hill in North Grafton.

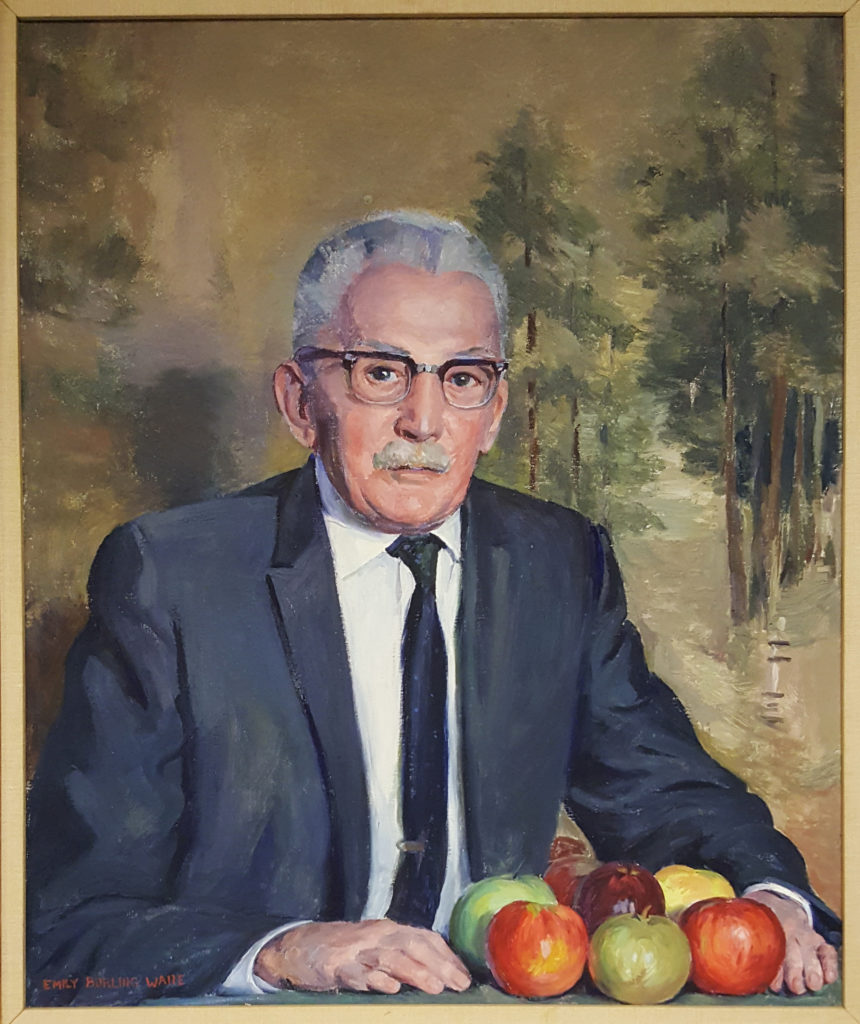

Russell Powell, author of “Apples of New England,” says Davenport may have done more to preserve heirloom apple varieties than anyone in the 20th century. Davenport worked with researchers at UMass Amherst to develop a list of 100 varieties worth saving and spent much of his life sleuthing – around New England, the United States, and beyond – for the missing trees from which he could collect scionwood. He was the Indiana Jones of antique apples, if you will. He shipped more than 12,000 scions around the world from the orchard he started in the 1930s. One of the apples in the New England Botanic Garden at Tower Hill collection is the Davey, a variety Davenport discovered – and by “discovered,” we mean he selected it for the particular traits he thought worthy of reproducing – in 1928.

The variety named by Stearns Lothrop Davenport in 1928 is still part of the collection.

As secretary of the Worcester County Horticultural Society, which had a long history of celebrating a rich diversity of agricultural produce at regular expositions, Davenport worked to maintain and expand his experimental preservation orchard project. After his passing in 1973, the Society, which at the time didn’t have its own land, collaborated with Old Sturbridge Village to give the heirloom apple varieties a new home. There the collection thrived, as scionwood was gathered for distribution each spring and apples were harvested for exhibitions and cider making each fall.

New England Botanic Garden at Tower Hill’s orchard being planted in 1990.

In 1986, the Worcester County Horticultural Society purchased Tower Hill Farm in Boylston. The property, sitting atop a drumlin – a hill carved by receding glaciers – overlooking the Wachusett Reservoir, had served as a dairy farm for generations. It was to be transformed into a botanic garden to teach the public the importance of plants, nature, and horticulture. And there was plenty of space to host Davenport’s heirloom apple collection. Staff and volunteers, led by WCHS trustee Gladys Bozenhard, harvested scionwood from the OSV trees, grafted the small branches to dwarfing rootstock, and cared for the saplings in a nursery at New England Botanic Garden at Tower Hill until they were ready to be planted.

The Washington Post interviewed New England Botanic Garden at Tower Hill CEO Grace Elton about the history of one of the apples in our collection.

Dedicated in fall 1990, the Frank L. Harrington Sr. Orchard, named for a fruit tree enthusiast and generous WCHS donor, contained 119 varieties on 238 trees. Over the years, New England Botanic Garden at Tower Hill staff distributed scionwood through a mail order program. They harvested apples for fall exhibitions. They sold some apples to local brewers to make cider. Tours provided opportunities to teach the public about the importance of biodiversity, pollination, and pest control. Media organizations such as Yankee Magazine, Victory Garden, and the Washington Post shared stories about the orchard near and far.

Why restoration?

Around 2011, the Frank L. Harrington Sr. Orchard started showing signs of fire blight, a disease historically associated with warmer, southern climates. Fire blight enters a tree’s tissues through flower blossoms and young twigs in the spring, as it is spread inadvertently by bees and splashing rains. The disease first kills flowers, then developing fruits, and young twigs, turning dead tissue black as if burned by fire. Infections can ultimately kill susceptible trees, spreading quickly through vascular tissue and creating reddish streaks in wood below the bark.

[See pictures of fire blight in New England Botanic Garden at Tower Hill’s orchard here.]

Prevention is the key to fire blight management, but is very difficult to achieve. Copper fungicides are effective, but must be applied repeatedly throughout the bloom period to prevent new infection. Copper is not effective against existing infections in wood; those must be pruned out to prevent further spread in an infected tree. With apples, resistance varies from variety to variety and selecting the proper rootstock will also impart resistance. Ideal conditions for infection, disease development, and spread of the pathogen are rainy or humid weather with daytime temperatures from 75 to 85 degrees Fahrenheit, especially when night temperatures stay above 55 degrees. Spring in New England is warmer and wetter than it used to be; now conditions most years are conducive to the spread of fire blight.

Spring apple blossoms in the orchard.

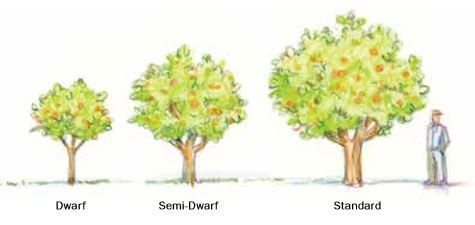

In addition to fire blight, the trees in the orchard are reaching the end of their expected life spans. Breeders continue to develop new rootstocks that aid in disease resistance, drought resistance, and, most importantly for commercial orchards, tree size. Most commercial orchardists grow their apples on dwarf rootstocks that produce abundant fruit on small trees that are easy to manage and easy to harvest but also have a shorter life span. Generally, the larger the rootstock, the longer the trees are expected to survive. Semi-dwarf rootstocks, like those use for the original Harrington Orchard, produce fruit trees that top out at about 15 to 20 feet tall and wide, and are expected to survive for about 30 years. Which is how long it’s been since the orchard was established at New England Botanic Garden at Tower Hill.

leafnetworkaz.org image

It’s time for the next chapter in the Davenport collection’s history. With the help of apple experts like John Bunker, founder of Maine’s Fedco Trees, and the support of people like George Harrington, Frank’s son, New England Botanic Garden at Tower Hill is growing new trees on fire blight resistant rootstocks with scion wood collected from the existing collection. We’re also re-purposing the wood into lasting works of art with the help of Upton woodturner Reid Gilmore. In the fall of 2019, the orchard will be removed. The land will lay fallow until the spring of 2021 when the saplings will be re-planted. A new orchard will arise, like a phoenix from the ashes, with the old varieties in the hands of the next generation of stewards, committed to preserving and sharing these varieties for generations to come.

***

Robert Burgess is the public relations manager at New England Botanic Garden at Tower Hill.

If you’d like to contribute to projects like restoring the apple orchard, please donate here.